The journey of memory loss is a long and winding road, with many twists and turns. The journey of memory loss sometimes seems like it is a never ending road.

The journey of memory loss is a long and winding road, with many twists and turns. The journey of memory loss sometimes seems like it is a never ending road.

The emotions of this journey are expressed for me in a Beatles’ song entitled “The Long and Winding Road.”

This haunting song describes one who loves another, who can no longer be found. The road leads to the door, but the one being sought has left the lover standing alone, with no way of making connection. The road is a lonely road for all involved because one is never sure that the connections are being made. Regardless of whether or not the connection is being made, the lover continues to love and continues to attempt connection. The song describes the wild and windy night, when the rain washed away, leaving a pool of tears,

“The wild and rainy night That the rain washed away Has left a pool of tears Crying for the day Why leave me standing here?

When I hear these words, I see the person whose mind is being washed away by disease, leaving the lover standing in a pool of tears, wanting so much to make a connection. In my interpretation of this Beatles’ song, I hear a story of love that goes on in spite of the situation. The lover cries out, “Why leave me standing here? Let me know the way.” The lover wants to know how to connect again…..how to reach through that which separates. Read and listen to the words while placing it the context of the journey of memory loss:

The long and winding road

The journey of memory loss is a long and lonely journey for all of those involved. There are many who cannot walk this journey with those experiencing memory loss. The journey can be too painful or it can be too frustrating. To walk with someone with memory loss takes time and sacrifice and the journey is filled with difficult choices.

I was one of those people that did not want to get on the journey. When I left university-level teaching and young adult ministry to enter chaplaincy, I was looking forward to working with aging populations BUT I DID NOT WANT TO WORK IN MEMORY CARE. Memory care made me feel uncomfortable, and I didn’t know how to communicate with those who were not at cognitive levels that were comfortable for me. I soon discovered that if I was going to work in senior health care, I was going to have to face my issues with dementia.

I had spent my entire life working in a world of words and higher level cognition. I was a person of the mind, who depended upon words to function and connect. How in the world was I to provide spiritual care in a world where words may or may not be helpful?

I pondered the situation, struggled with the situation, but didn’t feel I was getting anywhere. Then, one day, as part of my chaplaincy training, I experienced a pivot point moment of change when we had a person teach us about serving people with memory loss. The person presenting began by reading a portion from a book entitled, Tuesdays With Morrie. Let me share with you from the book:

“The Morrie I knew, the Morrie so many others knew, would not have been the man he was without the years he spent working at a mental hospital just outside Washington, D.C., a place with the deceptively peaceful name of Chestnut Lodge. It was one of Morrie’s first jobs after plowing through a master’s degree and a Ph.D. from the University of Chicago. Having rejected medicine, law and business, Morrie had decided the research world would be a place where he could contribute without exploiting others.

Morrie was given a grant to observe mental patients and record their treatments. While the idea seems common today, it was groundbreaking in the early fifties. Morrie saw patients who would scream all day. Patients who would cry all night. Patients soiling their underwear. Patients refusing to eat, having to be held down, medicated, fed intravenously.

One of the patients, a middle-aged woman, came out of her room every day and lay facedown on the tile floor, stayed there for hours, as doctors and nurses stepped around her. Morrie watched in horror. He took notes, which is what he was there to do. Every day, she did the same thing: came out in the morning, lay on the floor, stayed there until the evening, talking to no one, ignored by everyone. It saddened Morrie. He began to sit on the floor with her, even lay down alongside her, trying to draw her out of her misery. Eventually, he got her to sit up, and even to return to her room. What she mostly wanted, he learned, was the same thing many people want—someone to notice she was there.

(Albom, M. tuesdays with Morrie: an old man, a young man, and life’s greatest lesson. New York: Doubleday, p. 109, 110)

Hearing this, I was struck by the fact that if I was going to provide spiritual care for those with memory loss and for those impacted by memory loss, I was going to have to follow Morrie’s lead and lay down on the floor, so that I could enter the world of the other. I was led to understand that if I could meet them in their world, they would teach me how to connect in their world. One of my stated goals for that unit of study became to learn to lay on the floor, whatever that might mean.

Those who provide spiritual care for those impacted by memory loss are called upon to learn a new way. Spiritual care becomes much more than words. Spiritual care becomes incarnational, as one lies down on the floor with the persons impacted by memory loss, joining them in their journey.

As one enters the world of the other, one is reminded of the words of St. Francis, “Preach the gospel at all times and if necessary use words.” As time goes on in the journey of memory loss, words may or may not be helpful, but the loving presence of one who cares brings the full reality of God to the one with memory loss.

So what did I learn about laying down on the floor? I learned that laying down on the floor meant SITTING DOWN. Too many times, the people who interact with those with memory loss are in a hurry, and so they stand to communicate and serve. Many times, they are nervous about even being in the room, so they pace or stand waiting to leave. When I sit, I communicate that I have time and that I enjoy being in their presence. Sitting down means that I bring their attention to my face so that they see who I am and begin to connect my face and my voice. Sitting down and avoiding the perception of busy-ness allows the connections to begin.

There is NO ONE WAY to provide spiritual care to those impacted by memory loss. There are more than 70 different types of memory loss and each type has its unique subsets. Added to that, each person brings their own life history, their own experience, their own personality, and finally it become a journey of one that is completely unique and different from any one else on the journey.

There are certain ways of thinking and approaching spiritual care but there is no prescriptive way that works across the board. Providing spiritual care with those impacted by memory loss involves attentive LISTENING.

Morrie listened by getting down on the floor and laying next to the woman. Words were not spoken but he listened with his presence. As we lay on the floor, we listen for what brings meaning. We listen for ways to connect the heart of the individual with the heart of God. We listen holistically to find what brings identity, meaning and security to the one who appears to be slowly leaving us. We try so hard to not let our filters alter what we are hearing. We want to listen to the heart of the one whose memory is fading and whose ability to speak is waning.

To listen TAKES TIME. Morrie laid on the floor with the woman every day for as long as she was there and until communication had taken place. Those intending to provide spiritual care to those experiencing memory loss must be both frequent and consistent in their visits. In both of our secured memory units, I am recognized as the “church guy” and I have a variety of titles depending upon the background of those present; however, it brings joy to my heart that I am recognized, and, in some cases my voice is recognized. In order for this to happen I spend time with them daily. Understandably, daily visits are not possible for everyone, but frequent and consistent visits are important.

Providing spiritual care to those impacted by memory loss means that we FIND THE CONNECTING POINTS. Finding the connecting points comes as we lay on the floor and as we listen with the heart to the individual and to the voice of family. It is important to get to know as much of the story as possible of the one with memory loss so that the spiritual caregiver can find entry points for making the connections.

The entry point for connection can be found anywhere in the life cycle, but often is found in their childhood spiritual journey. The person with memory loss is completing the cycle of life which begins in the dependence of childhood, moves to the independence of adolescence, translates to the interdependence of adulthood, and then finally back to increasing dependency, as age and memory loss take their toll. As memory loss progresses, the individual moves back toward their time of childhood. I try hard to find out what their spiritual expression was when the individual was between eight and 10 years of age, because this may be the best way to make a connection to the level of cognition that they may be experiencing. What is the God language that the individual uses? What symbols of faith are meaningful? What might trigger spiritual memory?

MUSIC becomes a powerful tool for spiritual care. The part of the brain known as the medial pre-frontal cortex sits just behind the forehead and, when activated by music, triggers a memory connected with the music. Petr Janata, a cognitive neuroscientist at University of California, Davis says,

MUSIC becomes a powerful tool for spiritual care. The part of the brain known as the medial pre-frontal cortex sits just behind the forehead and, when activated by music, triggers a memory connected with the music. Petr Janata, a cognitive neuroscientist at University of California, Davis says,

“What seems to happen is that a piece of familiar music serves as a soundtrack for a mental movie that starts playing in our head. It calls back memories of a particular person or place, and you might all of a sudden see that person’s face in your mind’s eye.” For example, when I hear the song, “It’s a Small World After All, I have triggered for me a picture of my children and me riding in a boat going through the Disney experience. I can see it as if it happened yesterday. What do you see when you hear that tune? What other tunes trigger memories for you?

Music triggers memory and it triggers spiritual expression. Residents who cannot remember what they had for lunch, sing from memory the hymns of faith. On some of the songs, it becomes absolutely beautiful to hear the power of their voices as they sing deeply from the heart.

Ruth does not normally speak in ways that allow her to be understood. She is usually in her own world and, when not dozing, is generally a pleasant person. Ruth recognizes me as a spiritual leader and calls me “Father.” One of the joys of my life is to pull up a chair and sit in front of Ruth so that our eyes connect and a smile appears on her face. I will then begin to sing one of the old Gospel hymns. Ruth uses her own form of words but hits every note and stays on pitch. She radiates joy as she sings with me. Music becomes a connecting point.

When I do Scripture and Song in the memory care units, every week, I will have them say with me the words of John 3:16, and then I know that EVERY PERSON, no exceptions, will sing with me the song, Jesus Loves Me. Music carries an embedded spiritual expression in the hearts and minds of every person and becomes a powerful way to make connection.

ART is another way of making connecting points. Colors, patterns, or, even certain pictures will trigger memories. Whenever I see a print of the head of Christ painted by Warner E. Sallman, I think of my grandmother who helped me into the faith. Grandma had that picture of Christ hanging on the wall behind her chair and it was always a part of her life. Because it was a part of her life it has become a part of my life and triggers strong spiritual memories.

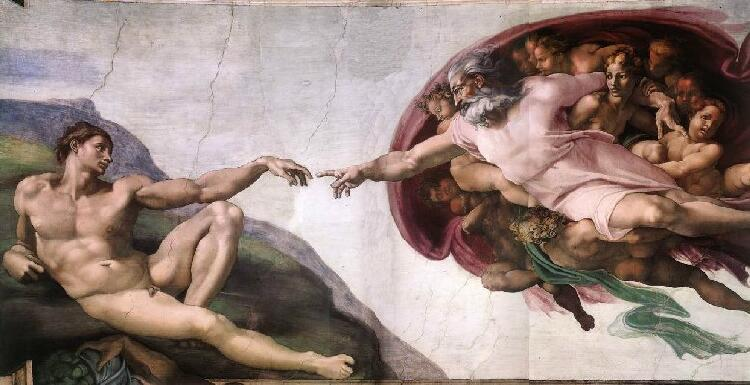

Notice, in this painting by Michelangelo, there is a way to understand the connection between God and man. This is actually a painting showing the creation of Adam but, to me, it also shows the deep desire of both God and man to connect. This picture carries the theme of spiritually connecting with those who have memory loss. There is a sense of lying down that allows the connection to happen. God continues to reach down to humans in the incarnation and reaches out with the hands of those into whom Jesus dwells. The spiritual caregiver becomes the hands and heart of God to the other. It is truly a spiritual connection brought about through the power of the Holy Spirit through living the Word.

One of my best teachers was a resident by the name of John. By the time I got to know John, he did not do much communication with words. John would answer questions with a “yes” or “no,” but otherwise had little to say. John was in his 90’s. His family described him as a gentle and quiet man, who loved his Lord and loved his family.

John was one who wanted human connection. Even though he could not speak, he would reach out to take the hand of those who passed by. He just wanted to be connected with the life around him. Holding hands with John became a powerful ministry.

You could tell that John loved to come to worship. He didn’t sing out loud any more, but if you watched him you could tell that his spirit was alive with song. During worship services I would sit him in the front row. so that when he reached out to take a hand, I could be the one whose hand he held. So during hymns, I would sit next to John and hold his hand as a way of helping him know that he was connected to the Body of Christ.

While the one with memory loss is still fully adult and needs to be respected as such, out of necessity, our ministry to those experiencing memory loss becomes the same ministry as to the infant recently baptized. The one with memory loss is losing brain cells and becomes increasingly dependent. At the baptismal service, Christian community promises to wrap around that young and dependent child. Christian community surrounds the baptized with the promise of prayer, support and love. It is the same for the one with memory loss, as Christian community wraps around the one with memory loss.

When we see the one lying in bed, unable to remember or communicate, we see the Body of Christ before us. We see each person as Christ and we reach out in love to say a prayer, sing a song and hold hands.

John helped me to finally understand that words just weren’t as important as I once thought they were. For John, words were spoken by holding hands and listening to hymns.

There is an old hymn that has come to mean a great deal to me, especially as I work with people in memory care. When John would reach out to take the hand of one around him, I hear this song and know that John was reaching out to God. The words of the hymn speak of the heart of one in depths of memory loss who connects with God by connecting with the humans that God sends to minister.

Lead me on, let me stand,

I am tired, I am weak, I am worn;

Through the storm, through the night,

Lead me on to the light:

Refrain

Take my hand, precious Lord,

Lead me home.

When my way grows drear,

Precious Lord, linger near,

When my life is almost gone,

Hear my cry, hear my call,

Hold my hand lest I fall:

Refrain

Take my hand, precious Lord,

Lead me home.

When the darkness appears

And the night draws near,

And the day is past and gone,

At the river I stand,

Guide my feet, hold my hand:

Refrain

Take my hand, precious Lord,

Lead me home.

See what else Steve has written about dementia and memory loss here.